Me, Myself, and Anthony Bourdain

examining my relationship with my father through my relationship with Anthony Bourdain

cw: discussions of suicide, addiction, and family issues

My father proposed to my mom in one of Anthony Bourdain's New York restaurants in the 2000s. They had been dating for four years at that point, and before the big event, my father approached a waiter and asked if he could put the engagement ring on top of the steak tartare he had ordered. The man wrinkled his nose, glancing skittishly to the side, before answering, "Chef really hates it when people do that." My father didn't know if 'Chef' was really there that day, but he didn't press the issue. He proposed over dessert.

Years later (but still before the divorce), my father met Bourdain himself on the street. After being properly starstruck, he commented that he had proposed to his wife in one of the man's restaurants.

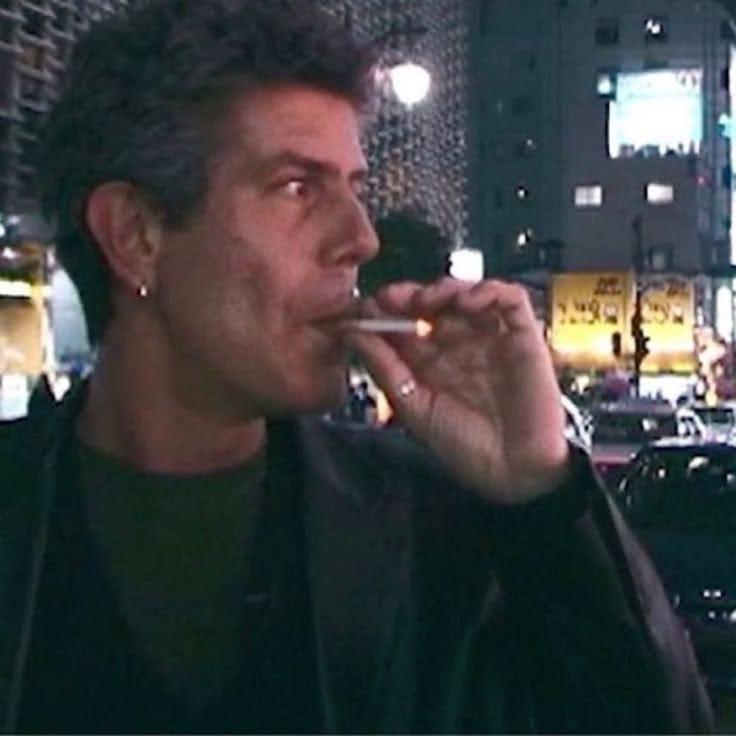

Bourdain gave my father a once-over and took a drag of his cigarette. "Please," he said, leaning against the exposed brick of the building behind them. "Don't tell me you're one of those assholes who asked to put the ring in the steak tartare."

I imagine a beat before my father said, "Of course not."

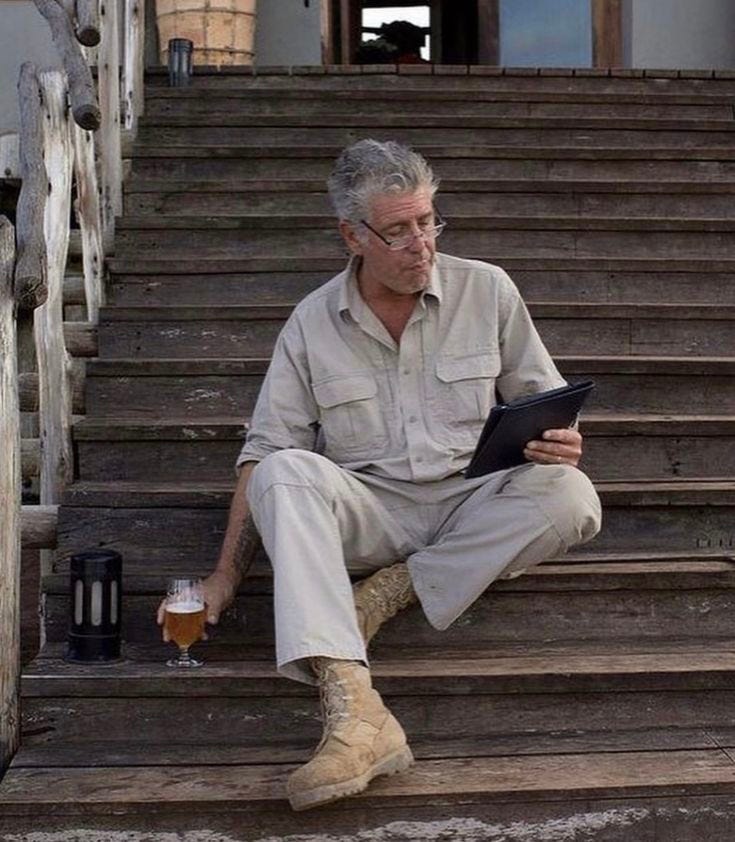

For those of you who have lived under a rock for the last twenty years, Bourdain is a celebrity chef most famous for his memoir, Kitchen Confidential, in which he exposes the ugly underbelly of the culinary industry. He also has several other not-as-famous novels, subsequent memoirs, and two cookbooks. His best shows include A Chef's Tour with the Food Network, Anthony Bourdain: No Reservations on the Travel Channel, and Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown on CNN. The man is a lauded writer and cook, famous for his razor-sharp wit, glib voice, and the hedonism with which he approaches food and travel.

I keep saying is, which is wrong. Bourdain killed himself in 2018.

I was thirteen in an airport when I heard about it, his face flashing on a TV next to the gate. I was still somehow affected by the recent suicide of Kate Spade (mostly I was given one of her wallets as a gift and it was the nicest thing I had ever owned), but this was much, much closer to home. Literally.

One thing about my father: he's a foodie. He can cook one hell of a steak and he loves to eat. For all the history between them, my mom trusts him to order for the family when we're out for dinner. When he took my sister and I to Paris, a case of gout did not keep him from all the wine, butter, and escargot he could have. He taught me how to heat up a shitty supermarket baguette in the oven to make it taste more expensive and fresh. He showed me his favorite dessert liquor before I had my first beer (Grand Marnier, for those wondering). He gave me my first oyster, but didn't press when I told him I didn't like it. He claps me on the back when I order my steak medium rare because "It's the only way to eat a steak."

Whenever I find myself brooding over all the aspects of my personality that my father gave me and that I hate myself for, I'm grateful to him for showing me how to enjoy food. Remorselessly, I order what I want at restaurants and let my friends squirm when I eat slices of sashimi. I was never a little girl who ordered chicken tenders. There was so much to experience, why would I limit myself if life was limiting enough?

"Remember, Isabel," he still says to me. "You can always keep cooking a steak if you take it out too early. You can't uncook it."

Back when I was less angry at him, it was the one thing I could count on to bond with him over. I was never the healthiest daughter, but I could always joke with him about whatever we were eating. He would ask me for my advice on what to order. Now, even with all the newfound tension between us, I know can always share a good meal with him. We don't have reservations about eating through tension if what we're eating is good.

As every child of divorce knows, the number one activity in your dad's house is watching TV. So, whenever my father sat down with me and my sister and wasn't in the mood for My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic, he would go back into his archived recordings of No Reservations.

I'm grateful to say that I grew up with the ability to travel. My father is the son of Greek immigrants, and my mother immigrated to the United States from Mexico and her mother is native to Madrid. It has always been important to them that I know that the world extends beyond the walls of the apartments that I grew up in. Many of our more adventurous trips were made without my father, but, in a way, I still went with him. If he knew we were going to Japan, for example, he would find Bourdain's Tokyo episode so we could marvel over sushi connoisseurs before I left. Pregaming the trip, if you will.

And yet, watching Bourdain's adventures across the world, I always felt small. I felt like I hadn't seen anything, only the same three neighborhoods that my international family resided in. But it didn't make me as embarrassed as curious as to what else was out there. Bourdain seemed to have the answers, and he was telling them to me with more patience (and sarcasm) than my father could muster on a good day.

I comb through my childhood and I find myself doing things for my father's attention more than I care to admit. I read and recited Greek mythology because I thought it would impress him. It didn't. I looked at him when my mother made some well-meaning comment that annoyed us. I made an early habit of forgiving him. Even now, I'm trying to get into the sorority that he likes (that doesn't have cocaine rumors).

One of the things I did as a girl was go through his bookshelf. I read extensively as a child, with a fervor that I am desperately trying to replicate now that I am in college. So, as a girl, I used to go through his thin, overflowing bookshelf. There, on one of those fateful days, I found Medium Raw, Anthony Bourdain's follow-up memoir to Kitchen Confidential. I had become very acquainted with the chef at that point, having followed him to Singapore, Rome, and Galicia through his shows. I had bought my father one of Bourdain's cookbooks for his birthday. And yet, as much as I tried (and I tried) I couldn't get past the book's prologue, in which Bourdain recounts a secretive dinner he was invited to with some of the most influential chefs of the 90s:

It's a fucking Who's Who of the top tier of cooking in America today. If a gas leak blew up this building? Fine dining as we know it would be nearly wiped out in one stroke...If this assemblage of notable chefs is not reason enough to pinch myself, then this surely is. This is a once-in-a-fucking-lifetime meal, a never-in-a-lifetime meal for most mortals, even in France! What we're about to eat is illegal there as it's illegal here. Ortolan.

I vividly remember consuming this one prologue again and again, the story getting old but never the writing. The way Bourdain described eating this poor, endangered bird, bones and all, fascinated me. I knew how to enjoy food, I thought, but I had never thought about what was in my mouth the way that Bourdain was writing about it: playing with the heat scorching his tongue, describing the crunch the bird's skull made beneath his molars, the Armagnac flavor that perforated it's guts. I think it was the most visceral thing I had ever read at that point in my life.

It was also the first time I had ever encountered the word 'fuck.' I didn't dare repeat it for years after, not even to my father. It felt strangely holy in the way that Bourdain's documentaries always were. Not perfect, not an angel, but a perfect reflection of what people were during a time that I didn't understand people. A reflection of the world during a time I had seen precious little of it. On an unrelated note, I developed an early tendency to run my mouth.

And then, when I was around twelve years old, Bourdain killed himself. I didn't know how to feel. My grandfather had died a few years prior, so I knew about death in the way that you know about an estranged uncle who asks your mom for money every now and then. I also knew that I didn't know Bourdain, or at least that he didn't know me. His work has been read by millions, his docuseries are even more widely consumed, by people with much more influence and importance than me (or, at least, twelve-year-old me). They say his death was impulsive, they found him in a German hotel during the filming of an episode for Parts Unknown. He had missed breakfast and dinner.

Suicide was not a new concept to me, but a very new reality. One that would revisit me. I once worried I'd loose my father to it. Then I'd be two for two, I guess.

My father was not the happiest with my choice of college. It wasn't the closest and, much worse, it was not the cheapest. I confessed to him once (through tears) that if he had told me not to enroll, I wouldn't have done it. If he told me to drop out right now, I would. And it's true. He has never understood that all he would have to do is ask, even now. And all he did was look at me and say, "I couldn't do that. It's your dream." Even though he had only discovered that it was my dream school of eight years a few months prior.

So, the plan was made. I would go to Chicago and bring my family to set up my dorm. We'd hit some nice restaurants, stop at the Art Institute, make a trip out of it. I was seriously looking forward to it, not only college but the idea of my family getting a good trip to remind them of me for the months they would be without me. True to form, after a dinner with my sister and father, he turned on the TV. "You'll never guess what I was able to record," he said, smiling to himself.

Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown, Season 7, Episode 2. Chicago. It was a great episode, truly. I had been to Chicago before, but seeing it like this, through the lens of a man who had raised me just as much as my father, made me feel secure in my decision. We pointed out restaurants, promising to go when they dropped me off, knowing it was physically impossible to visit them all in the three days we would be in the city. Even if it wasn't on that trip, there would be others. Still, it was nice to have the suspense of a plan, even if we weren't sure that the restaurants would still be open. It was a promise of tomorrow, of a flight and a meal we could share before I was really gone (I have always been gone, I think, in some way. But my family wasn't used to the idea of me not being physically around, at least. I had spent my life preparing to leave, they didn't expect to be affected by it as much as they were).

The day of the flight came. And my father never showed up to the airport.

It's a long story, but suffice to say that I ran my mouth. I wanted to get things off of my chest before I left and I got angry. I did my best to handle it with class, to keep my voice level. I didn't burst into tears. I could have. I didn't yell, I didn't scream. I could have. I didn't say a million things that I wanted him to know about me, about what I knew about him. Looking back, I sometimes regret that I didn't, knowing he wasn't going to show up anyways, even when I tried my best.

But he called me a week later (as if he could feel me beginning to build my own life from a thousand miles away). He felt that I hadn't been fair to him. That was fine, it was already a thought festering in my chest. Blaming myself is not a new phenomenon, even though I know better. What I didn't expect him to reveal that, when he decided not to come, he had been sober.

One of the writhing, feral things that live in my chest that I blame my father for is my need to move. To run away from anything that could be a relationship, an unwillingness to get comfortable. I don't know if he taught it to me or if it's in the blood (his family says I look like him, anyways. Hopefully they mean back when he had hair) but its a constant. When I don't run, when I stay stagnant, when I let my feet plant, that's when the universe punishes me. Because, like my father, I know myself. And I should know better.

On the day of the phone call, once I was done screaming at Lake Michigan, I walked back to the life I was building. I got on a CTA metra line with a gaggle of other freshmen I had assembled and we went to a neighborhood of Chicago we had never been before. We wandered through vintage stores we couldn't afford for a while before we ate at a local Mediterranean joint. The only Greek I can speak is the names of food, but I said them with enough of an accent to get extra sauce. We joined up five tables and all ate together, a group of strangers building their lives for the first time.

I stumbled on a Bourdain quote the other day:

If I'm an advocate for anything, it's to move. As far as you can, as much as you can. Across the ocean, or simply across the river. The extent to which you can walk in someone else's shoes or at least eat their food, it's a plus for everybody. Open your mind, get up off the couch, move

And it was familiar. I don't know if it was the timbre of his voice, trademarked, that made me feel as if I had heard it before. I don't know if I've watched whatever episode it was from before. But it makes me feel better, somewhere, to know that.

I encountered Medium Raw in my college's local library earlier this week. I've made it past the prologue, so I can't help but be a little proud of myself. I find myself in the pages, I understand myself. I understand Bourdain's suicide through his stories of frequent brushes with death and his attitudes about them so much I'm surprised he held out so long. I begin to understand my father, his addictions, his mind, his ideation of this man. My ideation of both of them.

It's the chicken and egg all over again and three times over. I wonder if my father was the way he was before he read this book. I wonder if he took cues from Bourdain in the way that I do from both of them. Which parts did he resonate with that I don't? I don't know which lines to avoid dwelling on or risk becoming both of them all over again. I wonder if, in the absence of either of them, would I be the way that I am? Would I still know how to order a steak? Would I still love to travel? Would I be constantly running? Am I unable to be in a relationship because of something that these men did to me or is it just me? In grasping at straws, am I dancing around that simple truth? How many times did I reshape myself because of these men? How many times did they fail to do the same for me?

I have lost at least one father to addiction, but my eyes are blurred and I cannot tell which one it was. I can't tell if this is a book in my hands or a phone on call. I only know that I need to eat something before the day is up. I can't not sleep and not eat. And I know how to enjoy it. I know that all that matters is to wake up and do things because I want to do them. I think they'd both be happy with that.

Anyone who's a chef, who loves food, ultimately knows that all that matters is: Is it good? Does it give pleasure?

The way that I know to tell when something is wrong is when I'm not eating. The way that I know to tell when I'm doing better is when I'm reading. I'm letting Bourdain back into my life and maybe things will get easier with my father. Either way, it's good practice. Almost as good as staying on the move.

This blog post is also available on my personal blog, where I keep prose I don’t post on Substack. Stop by for more of my writing (and a prettier blog layout).